Pictures: Renault by bike magazine.com Raleigh by HetisKoers.nl

Of all the (many) negative aspects of the US Postal/Discovery dominance of the Tour de France, for me, the most egregious is that in seven tours, only one of Armstrong’s teammates, George Hincapie, won a stage while he won 21 individual stages. If it was not all about the bike, then it was certainly all about Lance; his teammates were simply serfs to the master. (Yes, I know they won team time trials, but my point still stands). It was an efficient modus operandi, but seriously lacking in what might be termed “esprit des corps.”

In more recent years Sky have been accused of adopting the same approach in service of a particular team leader, but have generally shared the spoils more generously.Modern cycling seems to have increasingly adopted a monocular approach to the Grand Tours: teams line up with specific aspirations: targeting a particular jersey or maybe just looking for a stage win or two.

Race radios and team tactics have profoundly affected the sport for better and for worse. Barodeurs are few and far between and usually found in the ranks of the smaller teams. Gone are the days of an almost casual approach team hierarchies, take-it-as-it-comes strategies and riders seemingly having carte-blanche to take their chances.

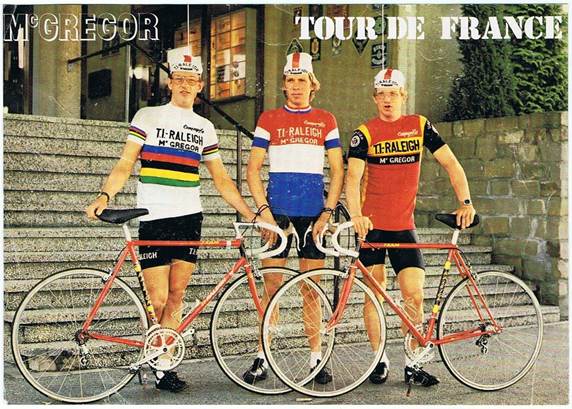

Historically, two teams standout as examples of a more freewheeling approach (pardon the pun), where wins were widely shared and the sense of camaraderie must have been (pardon the pun once more) sky high. Let’s start in 1980 with the Tour de France. 13 teams of 10 lined up for 22 stages which included two days of split stages. (In 1981 Bernard Hinault led a famous protest against this practice at Valence d’Agen and they magically disappeared in future editions. The Tour learned early that the Badger was not to be trifled with). Stages 1A and 1B were a 133kms road stage and a 46kms TTT; stages 7A and 7B were a 65 kms TTT and a 92 kms road stage. – impossible to conceive of today. The Raleigh team, led by no-nonsense Dutch boss Peter Post, had a viable yellow jersey contender in Joop Zoetemelk, the dogged Dutch veteran who had finished second in the Tour 5 times between 1970 and 79. As a supporting cast they had Jan Raas, Henk Lubberding, Bert Oosterbosch, Gerrie Knetemann, Cees Priem, Leo van Vliet, Paul Wellens, Bert Pronk and Johan van de Velde on the roster; frankly, this was an embarrassment of riches. By the time the race reached Paris, Zoetemelk was in yellow and Van de Velde in white as best young rider. Raas had won three stages, Zoetemelk two and individual wins were secured for Lubberding, Oosterbosch, Priem, and Knetemann. Oh, and if that wasn’t enough they won both team time trials, setting a new standard for preparation and discipline in that event. A total of 11 stages or half of what was on offer. Dominance, but not just with one rider reaping the glory.

In 1984, Laurent Fignon, returning from his 1983 Tour triumph, led the Renault-Elf team. (Hinault had skedaddled in the off-season for Bernard Tapie’s new La Vie Claire team). The bespectacled Frenchman was undisputed leader of his merry band of young professionals and as the new superstar of cycling might have been expected to demand total subservience in pursuit of another Tour crown. Not quite. Twenty-three stages and a prologue lay ahead for the 170 riders – quite a rise from just four years earlier – as the race left the outskirts of Paris at Montreuil. Renault dominated throughout, winning stages 2, 3, 7, 8, 12, 16, 18, 20 and 22. Fignon won five, Marc Madiot, Pascal Jules and Pascal Poisson each got one and the team claimed the team time trial. Vincent Barteau spent 12 days in yellow, Fignon seven. By Paris, the team had 9 stages in the bag, overall victory plus the team classification, 2ndin the team points competition and the white jersey for best young rider being won by a fresh-faced American kid called Greg Lemond. By any standards it was a performance of stunning team work. One can only imagine the sense of camaraderie at meal times as the successes kept coming for both teams and each rider fully feeling that they were not just true contenders, but setting the standard for others to beat.

What makes these two teams exceptional is that both had legit yellow jersey aspirants (who were ultimately successful) yet did not metaphorically put all their eggs in one basket. Both squads were led by wily ex-pros who were tactical geniuses: Peter Post and Cyrille Guimard, and both were strong in depth with a great mix of specialists and all-rounders.

Appropriately, given that we’re discussing the Tour, I’d like to close by quoting the great French novelist Alexandre Dumas, whose Three Musketeers had a motto of “all for one and one for all.” Raleigh and Renault didn’t just enter cyclists, they sent musketeers with attitudes that could be described as “swashbuckling” – taking advantage of all opportunities and chances. While dominance can get a tad predictable and boring, we should be so lucky as to see their likes again.

ANother test comment to check if working – going to stick to the no emoticons Rule?!

Can I suggest, re formatting, that there is a line break between paragraphs?

Still a good article though!

David – Indeed – if only it worked! Been trying to get the format on the Post page to reflect the formatting in the actual Post but somehow, somewhere, the line breaks are being removed! I’ve actually put double line breaks into the Post but when they come up on this page they get removed. On the list to try to resolve though!

Oh – Anyone want me to try to find an emoticons Plugin?

How times change. More professional? Teams can’t afford too may riders with the ability to win stages?

I was reading this week on the demise of the UK domestic scene with teams folding (One Pro Cycling being the latest) and fewer events. All leading to a thinning of the feed for the Pro teams – or at least driving any quality UK up and coming riders to the continental scene – back to the old days.

Also adding a comment for RSS testing.

Hello all!

Testing the comment section. V lives on from the ashes. Great article, wiscot!